60 remarks on Love Between Women

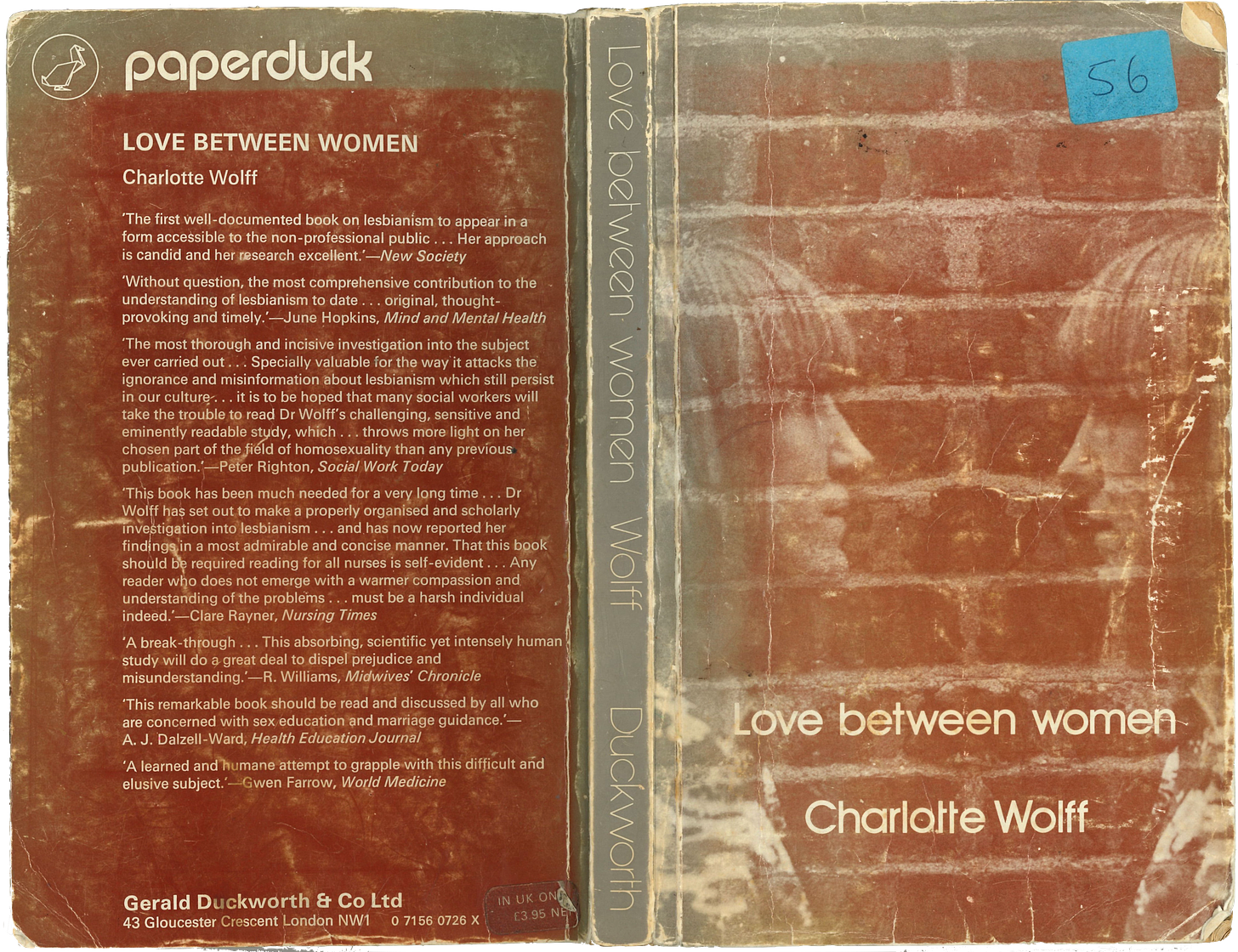

Love Between Women is a study of lesbian life first published in English by Charlotte Wolff in 1971. It was her first study of gender/sexuality, followed by Bisexuality in 1979. Previously her books had been on hands, palmistry and gesture.

I finished reading the book in May, felt overwhelmed by it, and had no idea how to synthesise the endless notes I had made, so I present them here, edited down as a series of remarks.

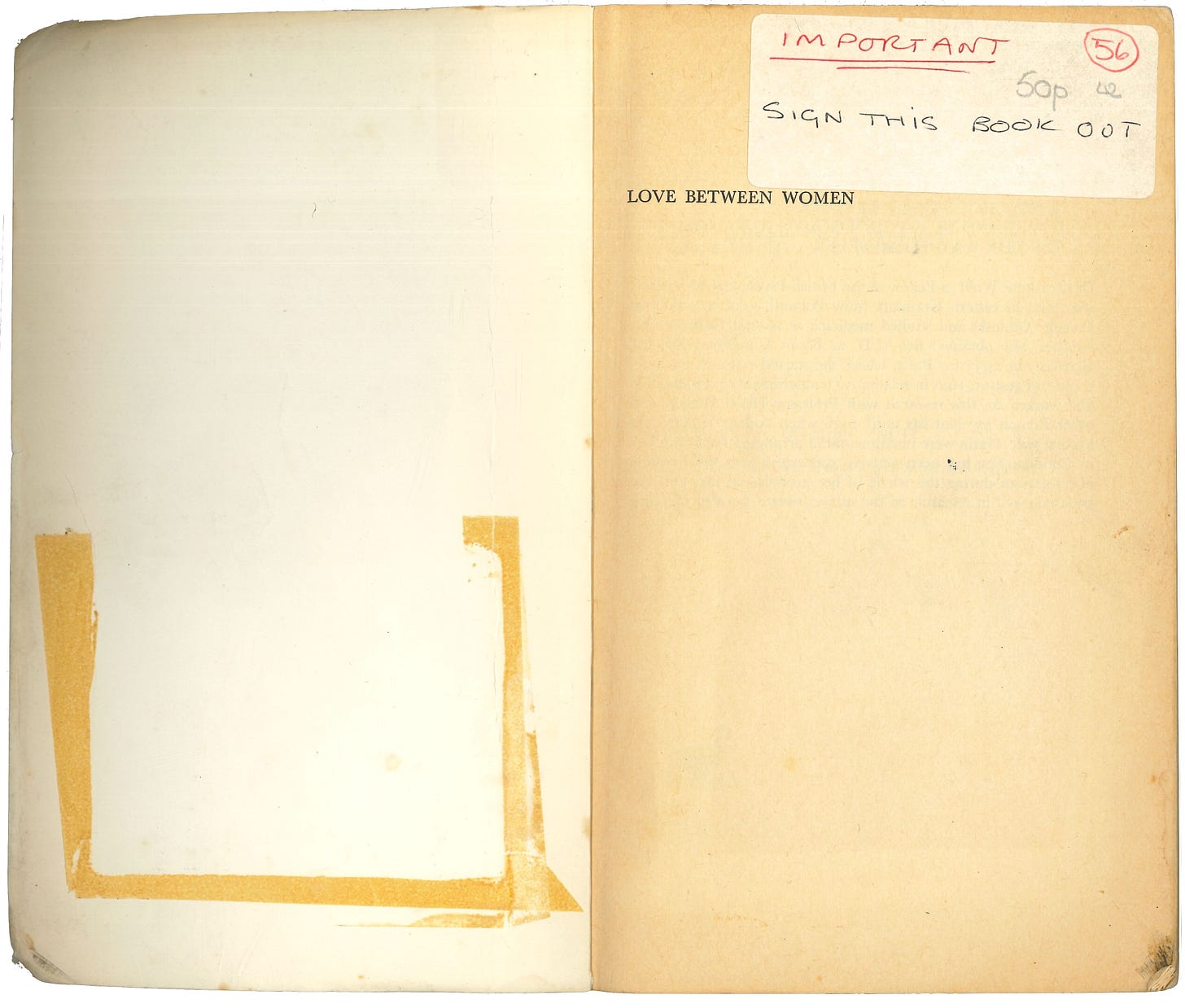

My copy is a former library book, as were most of the Wolff books that I ordered online after I first discovered her. I love the label on the inside: IMPORTANT and SIGN THIS OUT and 56 and 50p, all in different pens. I can’t trace which library it came from, but I get a sense it was in a small town library in the UK. I wonder how it negotiated and survived Section 28.

There is one review on amazon: “The book was in good condition and in general it is a good book, easy to read, But it is not what I expected!! I found quotes about this book describing it as milestone. is not!”

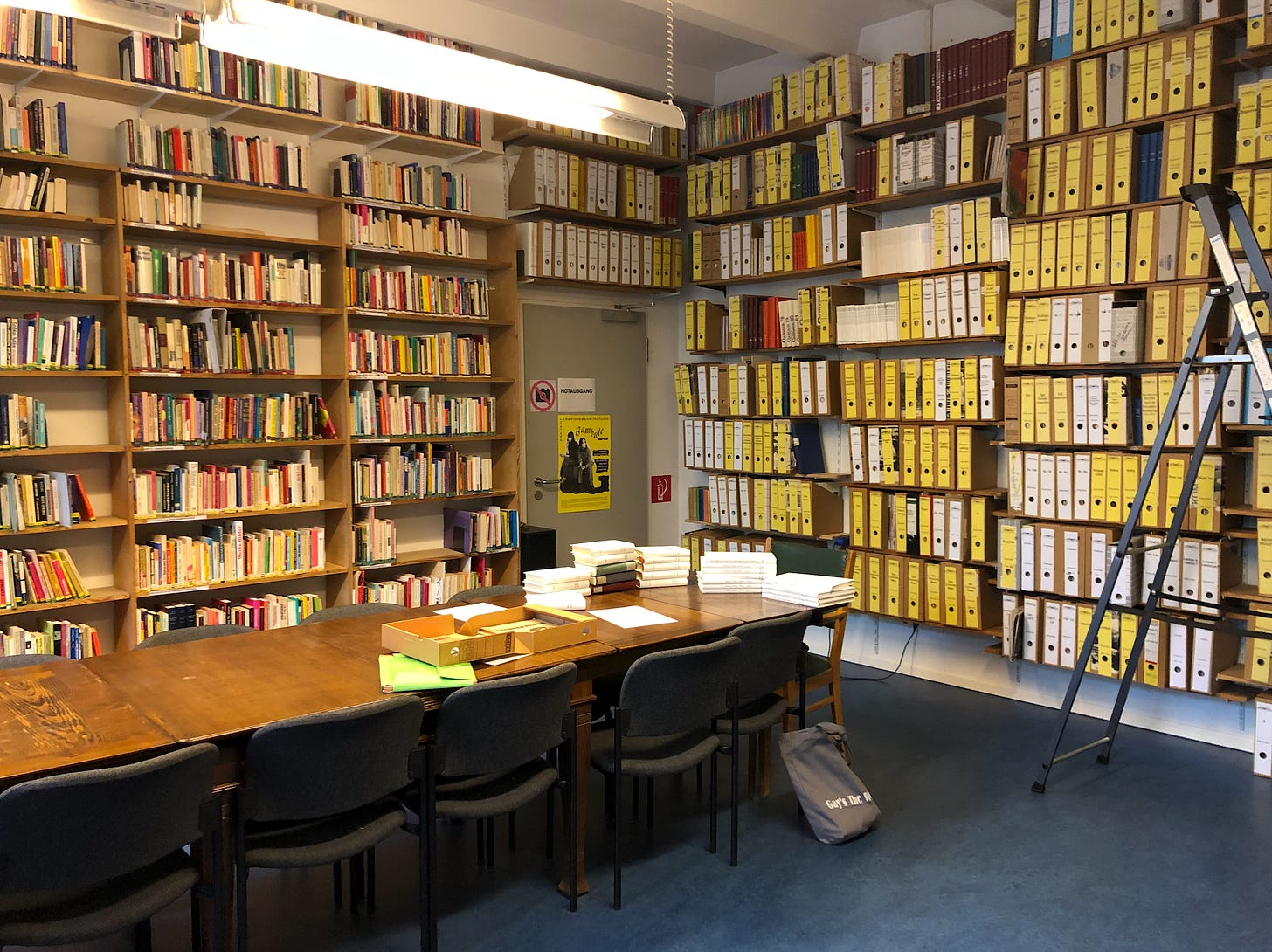

I paid £3.90 for it, but the hardback is collectable and expensive. When I visited Spinnboden, a lesbian archive and library in Berlin (pictured below), there was a copy of Love Between Women in a locked cabinet, with Wolff’s signature in it, kept safe, away from the open shelves. I was shown it quickly before it was locked away again.

Wolff states, in the preface, how quickly the ‘homophile world’ is moving. Even in two years since the first publication of Love Between Women, she had to made additions in the second edition, published in 1973.

Wolff says lesbianism has been neglected as an area of study. She claims there has been no book solely on lesbianism until this one. I’m not sure how true this is.

The book was written in co-operation with two UK lesbian organisations: Kenric (which was founded in 1965 and still exists as an organisation) and the Minorities Research Trust (which was founded in 1967 but no longer exists). I contacted them to see if they have any records of their interactions with Wolff but I haven’t heard back properly yet.

In preparation for the book Wolff asked ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ people 90 questions. The ‘normal people’ were the ‘control group’ and they were straight. She says she calculated ‘truth’ from the answers given.

I am interested in the tradition of the interview and its parallel with oral history making, as it is used today by a number of groups and writers on gender, sexuality and race: such as in the work of Mireille Miller-Young, the NYC Trans Oral History Project, among others. (I tried to start a project on the London Lighthouse, a hospice for the care of people with HIV/AIDS, and interviewed the amazing Beattie Dray, one of the first nurses to work there. I’m interested in the space oral histories give people but not sure I am the best interviewer).

Wolff thanks her friend Audrey Wood O.B.E. for her help with typing.

Wolff defends an ‘emotional’ conception of sexuality and says that homosexuality is foremost an emotional disposition, from which sex is secondary. That homosexuals can live with their homosexual friends for years without ‘any sex acts’ is proof of this, she says.

Wolff defines ‘perversion’ as a fixation of the libido on one organic system, which may be the sexual organs or other parts of the body, which can lead to destruction. But she also says that the ‘dislike of the pervert is nothing but the unconscious fear of being perverted, and reflects self-hate’.

Wolff compares homosexual identity to Jewish identity a number of times in the book, as she does elsewhere.

Wolff says persecution leads to various qualities: assertiveness and/or irritability and/or defensiveness and/or defiance.

Patriarchy, Wolff says, explains greater persecution, both legally and socially, of male homosexuals but also other sexual minorities.

Wolff says the doctor Georg Groddeck mixed up homos (‘same’ in greek) and homo (‘man’ in Latin) and this had great consequences.

Wolff says the analyst Sánder Ferenczi coined the term ‘homoerotic’ in 1917. He also coined a distinction, she says, between objective and subjective homoeroticism. The subjective is feminine; the objective fits into ‘normal’ categories of masculinity. Wolff adds another word: ‘homoemotional’, which she says needs time to embed.

She talks about Sappho and her ‘sophisticated’ love of beauty, grace and charm. An analysis of one of Sappho’s poems also leads to the statement: ‘Sadness is part of ecstasy, and both belong to the original image of sapphic or lesbian love’. This is ‘intrinsic’, she says, that leads Wolff to a defence of the superiority of lesbianism; that lesbians process ‘a more global, all-embracing love-potential’ than male homosexuals. She goes further: Lesbians have two ‘distinct features’: (i) a ‘highly aesthetic quality and reverence for beauty’, and (ii) ‘intense emotionality’.

She says student-teacher relationships are a key part of lesbianism.

For this study, she interviewed some people on the phone. She protected the privacy of the people she spoke to, in case they lived in fear of being outed or of losing social status.

Wolff turns to a chapter titled ‘Some Psychological Theories of Homosexuality’. She argues, that the ‘first theory of homosexuality is a vision of great poetry’.

She talks about the three ‘hermaphroditic’ types in Plato’s Symposium: one was a man-man type (those who love only men), the second a woman-woman type (who can only love women), the third a man-woman type (who can only love women). I don’t really follow.

She returns to Freud: that all humans are originally, ontogenetically and phylogenetically, bisexual (which she defines as hermaphroditic). This comes up in all her writing.

She then talks about Freud’s essay ‘The Psychogenesis of a Case of Homosexuality in a Woman’ (1920), then Dora, then Klein – that ‘babies, from six months onwards, perceive their parents as one rather monstrous hermaphroditic unit’. I’ve never read the Freud essay but would like to.

She says that Hirschfeld and Steinach’s research, reductive to biology, was usurped by Freud (though not always chronologically), which has its basis in ‘bio-psychological history’.

She says that the ‘memory traces of our early hermaphroditic structures will never die’.

Wolff then embarks on ‘A Theory of Lesbianism’, which she says has been almost entirely neglected.

She says the most recent research in sexology points to the origins of sexuality in the endocrine glands during foetal life. (It made me think of what Jules Joanne Gleeson and Elle O’Rourke, the editors of Transgender Marxism (2021), call Paul Preciado’s ‘endocrino-romanticism’ but maybe I misunderstood.)

Wolff says she aspires to a ‘mosaic theory’ of lesbianism, as she wants to study it separately but build it to a greater whole.

It strikes me as interesting and significant that Wolff engaged with sexuality studies outside of the university. For example, when she is invited back to Berlin in 1978 by the activist Ilse Kokula, she spoke with many different women’s and lesbian groups, frequented social centres and squats – such as the groups L.74 and L.A.Z. (the Lesbisches Aktion Zentrum) – rather than university or academic settings.

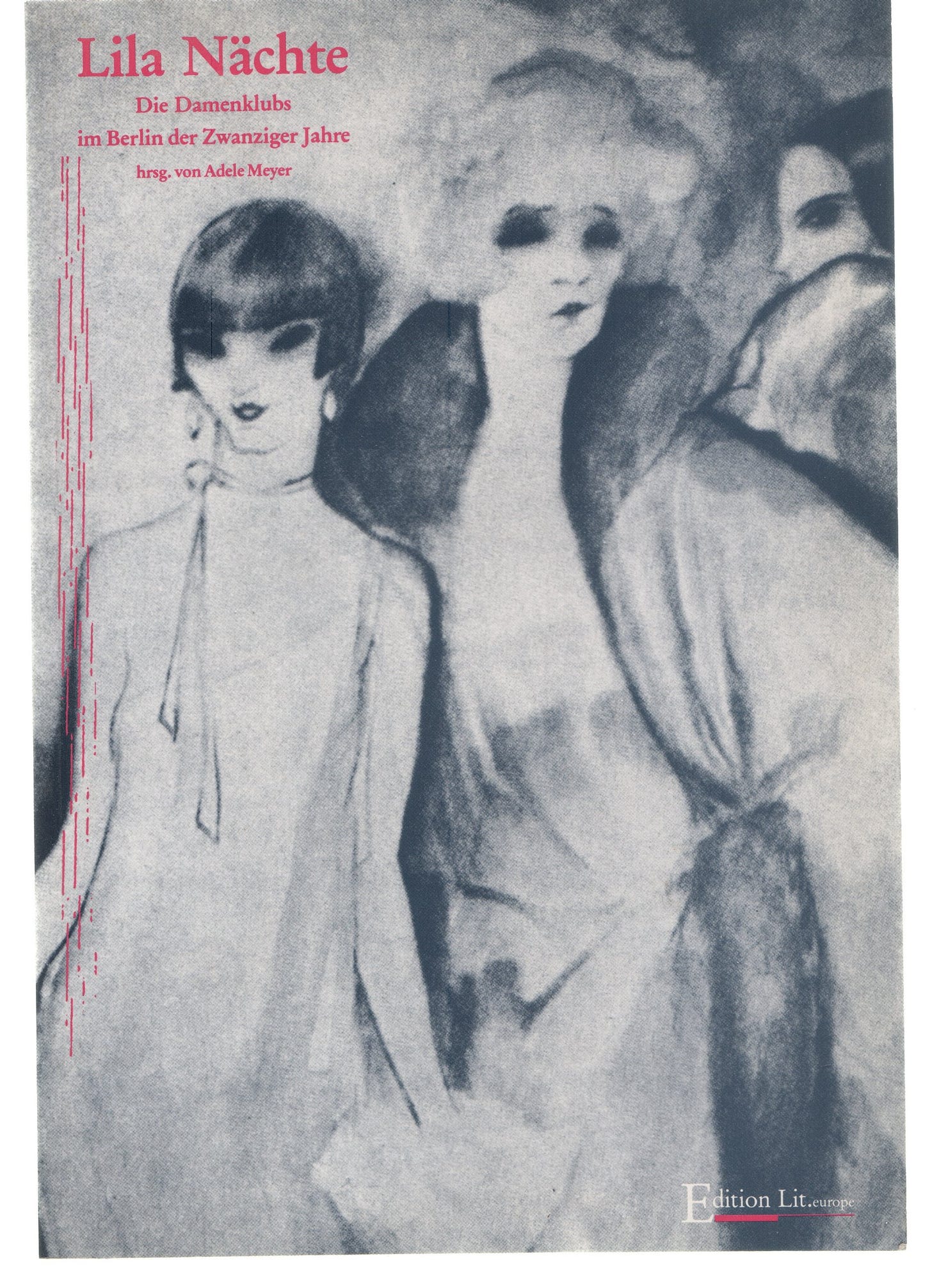

Ilse Kokula wrote a number of books, including Weibliche Homosexualität um 1900 in zeitgenössischen Dokumenten (1984). This could also be said of the overlap not just of activist layers of queer cultures but also the night-club scenes. It is interesting perhaps that Wolff ended up writing a biography of Magnus Hirschfeld as late as 1986 and lived in Berlin as an out lesbian doctor when the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft was open, but she never went there. Wolff talks about the clubs she went to in her autobiography, for they were more (if not, as) important, many of which appear in Adele Meyer’s history Lila Nächte: Die Damenklubs in Berlin der 20er Jahre (1994), which is introduced by the Ilse Kokula.

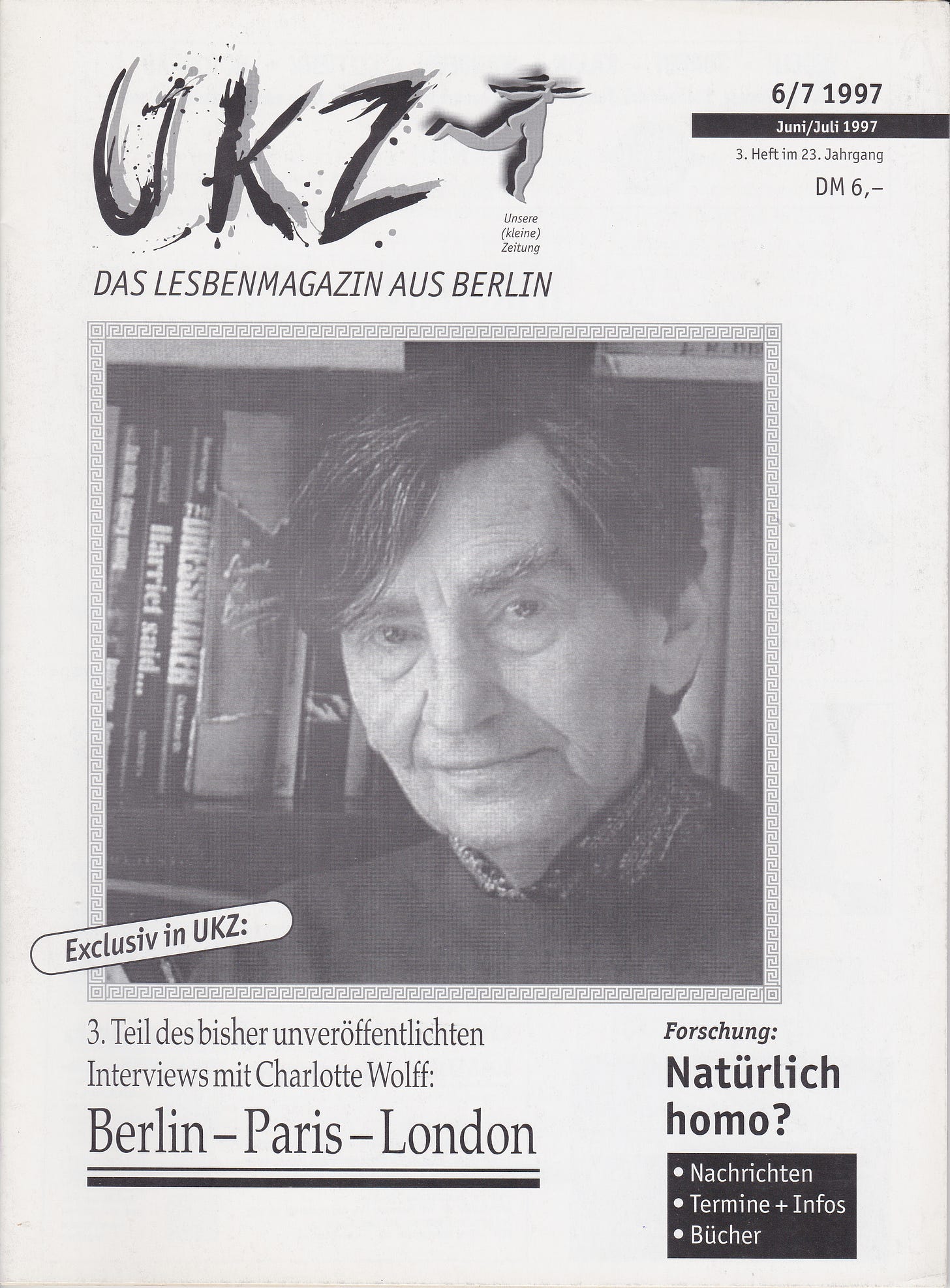

Just over a decade after Wolff died, and two decades after her visit to Berlin, the magazine of the group L.74, called U.K.Z. (Unsere Kleine Zeitung) published an extended tribute to her. It was edited by Ilse Kokula at the time, and there’s also an interview between Kokula and Wolff, where they talk about various lesbian organisations and publications, the importance of sociality in groups, the broadcast of the second documentary to depict lesbianism The Important Thing is Love (1971) (available to watch here) in which she features (!), among other things. There is also a picture of Wolff with the artist Gertrude Sandmann at the women’s bookshop Labrys once on Yorckstraße, there’s also a picture of Wolff with her partner Audrey Wood, both with glasses of wine in their hands.

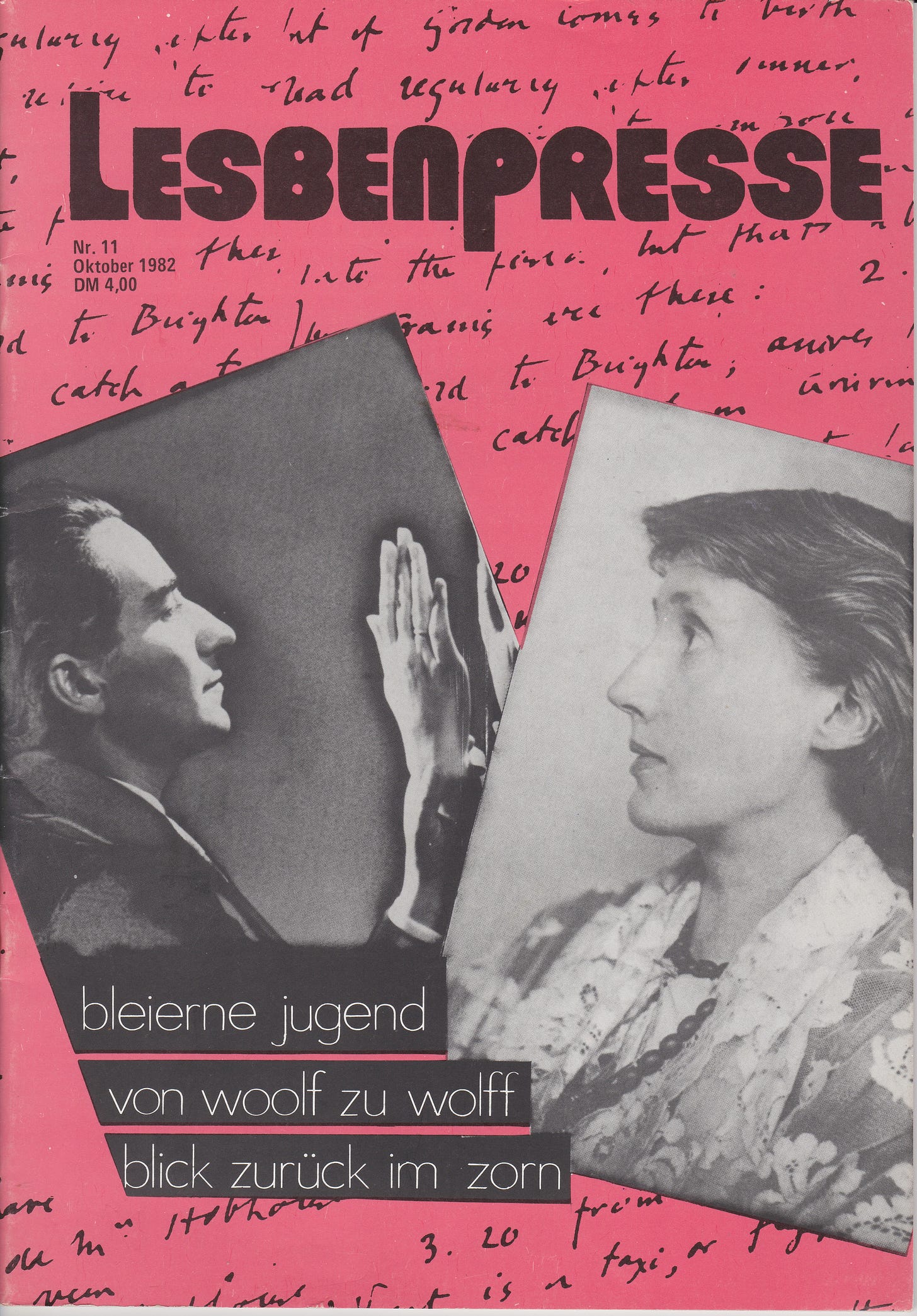

At Spinnboden I also looked at an edition of Lesbenpresse from October 1982 (pictured below), with the most incredible graphic design. Inside was an essay entitled ‘Lesbianism and Bisexuality in the work of Djuna Barnes and Virginia Wolff’ by Wolff, written in 1980. The article is scattered with adverts for the 1983 Lesbenkalender. I set up a saved search on eBay. Wolff had read Woolf’s hand, but not Barnes’ hand. There’s also a reproduction of the portrait of Wolff by George Hoyningen-Huene. There’s also an extract from Wolff’s first memoir. There’s also a word puzzle.

To return to the book: Wolff says that the father is an alien to the child, italicised as such and she outlines a psychoanalytic account for the origin of the disposition of loneliness in girls.

Wolff says some fucked up things about trans* identity, within a model of psychological or pathological reduction. Lesbianism, at this point (or at least in Wolff’s case), was, to use Heather Love’s language, less capacious.

There’s a sudden moment of pseudo-marxism: ‘The era of high capitalism stood at the cradle of psychoanalysis, and the shadow it cast over it has never vanished’, she says.

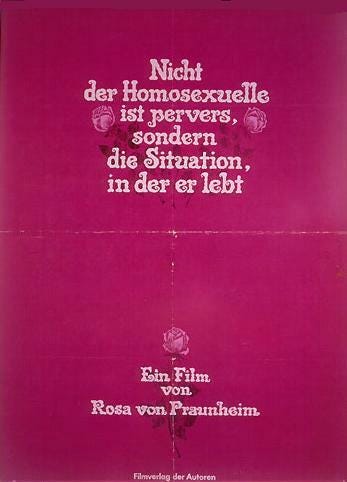

Wolff’s writing, as with much work in the history of gender and sexuality from this time, conflates gender and sexuality. To have a certain sexuality is to carry an associated gender identity. (It makes me think of the taxonomies in Rosa von Praunheim’s It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But Rather The Society In Which He Lives, made in 1971, the same year Wolff published Love Between Women. I wonder if Wolff and Praunheim ever met.)

Wolff reports asking her interviewees why they lived as lesbians and they unanimously replied ‘I had no choice; it happened that way’.

Wolff argues that lesbians are at the centre of the struggle for liberation; in a refusal to be subordinated in the public and private spheres.

Wolff says that a society that fully accepts the universality of bisexuality will break up the family. Cf. Mario Mieli?

Wolff says that when lesbians in heterosexual marriages leave those relationships they encounter the ‘spontaneity of homosexual society’.

Wolff sustains a Lamarckian (perhaps also Freudian) account of inherited trauma: ‘The effect of a threat to life and limb lingers in the ancient parts of the brain of those who belonged to persecuted units’, she says.

Wolff says she mostly interviewed working- and lower-middle-class lesbians: secretaries, typists, bank clerks, nurses and teachers.

She says that most of her interviewees (those she didn’t speak to on the phone) came by car or train from the country or the suburbs; that she developed the habit of looking out of the window at the appointed time, to ‘catch a glimpse of the stranger’.

Wolff says she received everyone as a friend.

At the time she lived at 10 Redcliffe Place, just east of the Brompton Cemetery in Chelsea. Imagine her peaking out of the window as her interviewees arrived. (A friend of mine was staying nearby as I was writing this, and she walked over to look at the house. She reported back: ‘It’s an incredibly hot day. I walk through Brompton Cemetery and the smell of jasmine is so strong I almost felt sick. I pass the grave of Emmeline Pankhurst and try to remember if maybe she was actually bad or if that was someone else. I try to photograph the hands of angels. A man remarks on how hot it is. I agree. The house is almost directly beside the cemetery. The streets look typical of west London. Big terraced houses with columns at the front, though her street is fancier than those around it which look a bit shabbier. Bizarrely when I went round the corner the first thing I see are two England flags and a Union Jack flying above some kind of mini vineyard. It says ‘lady callas’ above the door.’)

Wolff says paranoia is endemic in the gay/lesbian community and it has a social origin.

Wolff defines the family as a ‘groupage’ in a patrilineal society, which often covers nothing but ruins.

This sentence stood out: ‘I saw remnants of the Tsarist era in the USSR when I visited spas on the Black Sea in the late 1920s’.

Lots of stuff to do with parental roles and sexuality that gets a bit tiring.

On siblings and sexuality: Wolff says lots of lesbians don’t have siblings. She refers to a paper about birth-order order and sexuality. She also says that mothers of homosexuals are frequently older than in the test group.

There is a constant return to a problem of nature in Wolff’s work. Given she thinks that bisexuality is natural, any identity of gender or sexual variance, is merely an expression of nature. I prefer an anti-Hirschfeldian line: anyone can be gay, and it’s even better if it’s against nature. Or as an 1982 interview with Wolff is titled: Naturlich ist homosexualität am leichsten erlernbar, or naturally homosexuality is easily learnt.

Asked if they had any guilt feelings about their homosexuality, most of the lesbians Wolff interviewed replied simply and clearly: none.

Wolff says there are three types of aggression: (i) that stems from rejection; (ii) that stems from frustration; (iii) that stems from an erotic drive. She then talks about Winnicott.

There’s a short paragraph that simply reads: ‘Lack of inhibition is the result of inhibition.’

Wolff says shyness is often a lesbian trope and that sex dreams are more common for the lesbian-identified group than the control group.

Wolff asks her interviewees about pets and found that most of them had one or more animals. To quote: ‘All but four had one or two cats. One kept white mice in addition to a cat. Four lesbians who loved and reared dogs lived in the country. The question whether the cat, symbol of the female, enjoys special favour among lesbians cannot be answered. It is conjuncture to say that it might be so.’

She says that lesbianism resembles freemasonry in some respects and finishes the book with the declaration that ‘information is education’.

The book says a lot more and this list could go on but I stop here.

Thanks for reading. I’ll try to not write so much next time. If you like my newsletter, please feel free to forward onto friends who might be interested – or share online. Thanks to Hannah for going to look at Wolff’s house and reporting back! Thank you also to Spinnboden for their hospitality and for help with the image reproductions. Copyright is theirs. Hope everyone is doing well ♡