Disappearing Uncles

On Baron Schey and other relatives

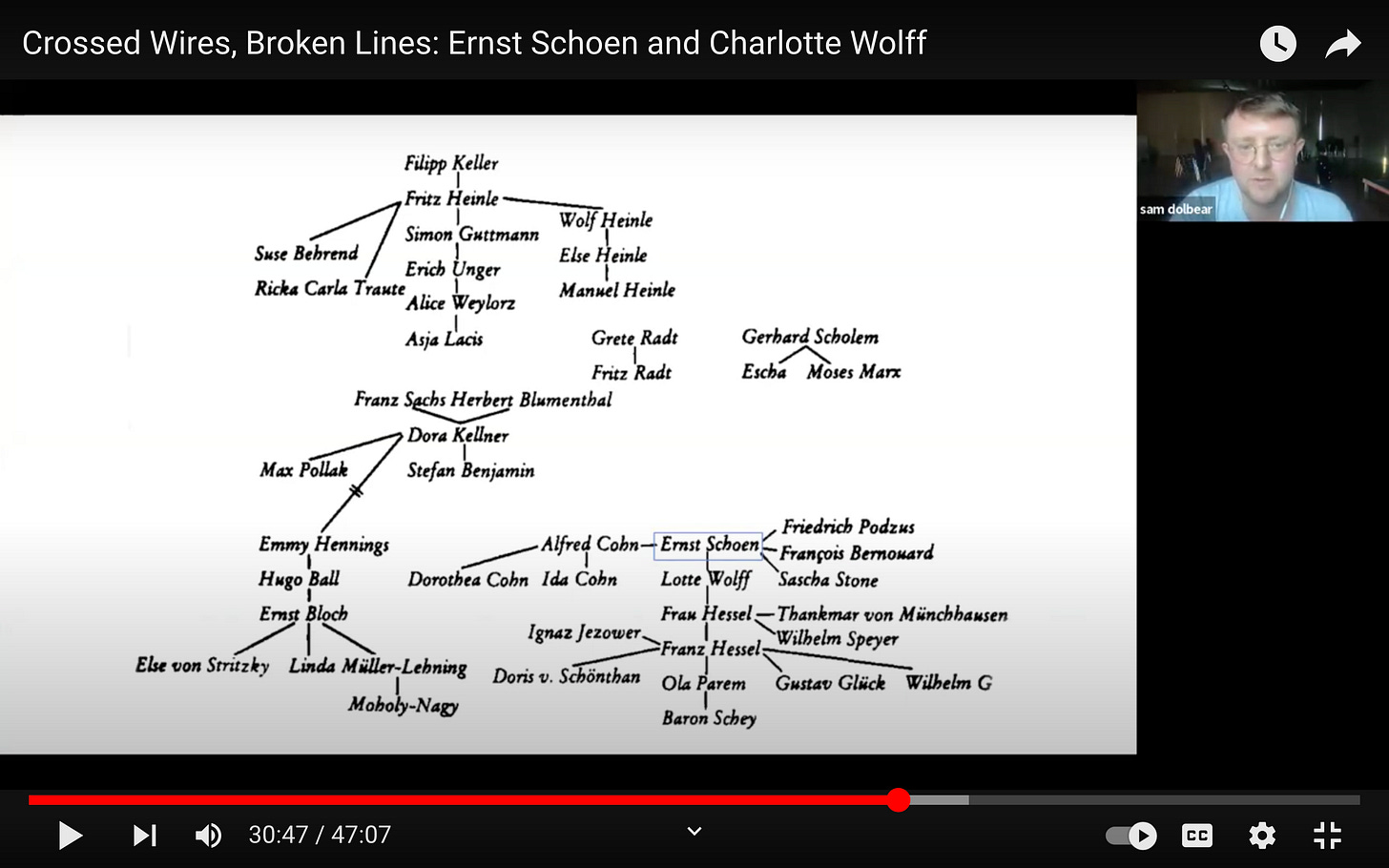

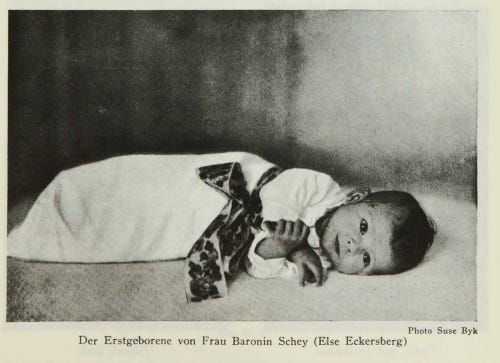

When I did a talk with Esther Leslie at the Insider/Outsider festival (archived here), the organiser Monica Bohm-Duchen noticed the name Baron Schey on a slide of the diagram that shapes much of my research. Working down the main spine of the bottom right-hand cluster, there’s a line of people I’ve now done work on: Ernst Schoen (review of our book here), then┇Lotte Wolff (book here soon), then┇Helen Grund (related review here), then┇Franz Hessel (one day something on this), and┇Ola Parem (nothing as of yet). At the end is Baron Schey, about whom I only really had a photo (below) from Der Querschnitt magazine, uncovered when I was looking for pictures of Doris von Schönthan as a hat model (paper slides here). As the caption reads: The firstborn of Mrs Baroness (Else Eckersberg). (Gifts and gratitude to anyone who clicked on any of those links.)

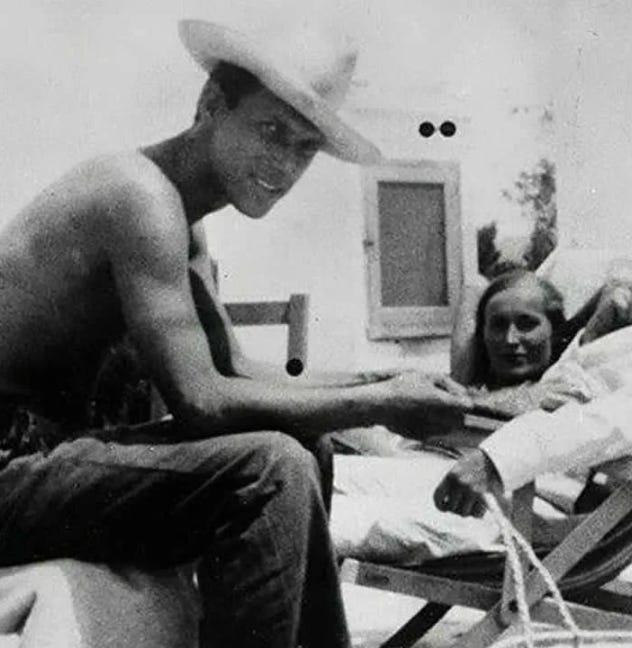

Monica Bohm-Duchen recommended me Kathy Henderson’s book My Disappearing Uncle, about her family’s relation to the Scheys. It turns out that Benjamin’s Schey is Philipp, shortened to ‘Pips’, who, according to Henderson, married three times – first to Lily von Goldschmidt-Rothschild, who died, then Else Eckersberg, mother of the baby in the above picture, and then, after they divorced, to Olga Paretti, listed as Parem on the diagram. Parem visited Benjamin in Ibiza in 1932 and he had proposed marriage, which she refused. A well-known image of Benjamin on Ibiza (also below): to the right of shirtless art historian Jean Selz in a hat is Parem, staring out at the camera.

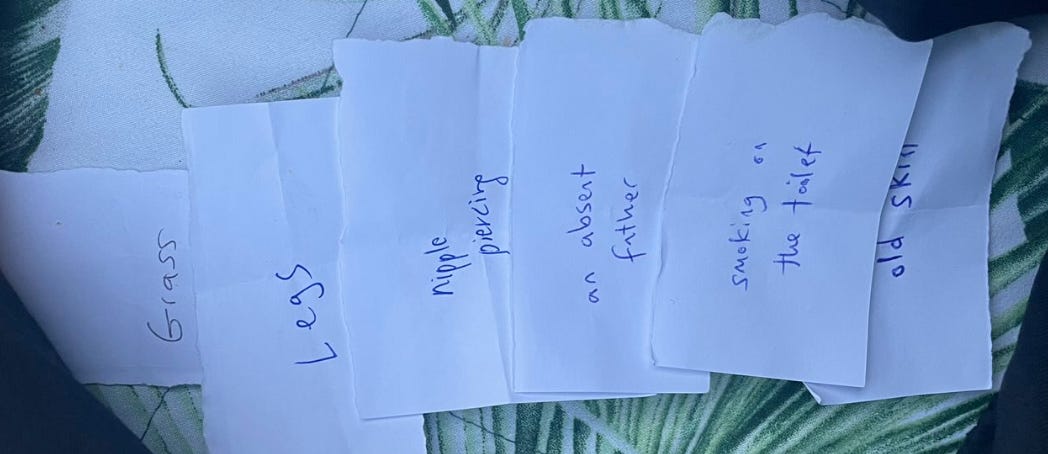

To play the game ‘preferences’, each player separately writes out six things on slips of paper and puts them back into a central pot. Each player then pulls out the same number of slips at random. That person then privately ranks the slips in order of their preference, takes a picture to remember the order, and returns them to the group, who then have to discuss the order they think the person ranked them. When I played the other week, 𝒶𝓃 𝒶𝒷𝓈𝑒𝓃𝓉 𝒻𝒶𝓉𝒽𝑒𝓇 appeared on a slip, and there was a shift in our conversation from placing it at the bottom of any list to thinking that the absence of a bad father can be good, and the absence of a neutral father (if that’s possible) might be on a spectrum between bad and neutral. Ultimately the player placed 𝒶𝓃 𝒶𝒷𝓈𝑒𝓃𝓉 𝒻𝒶𝓉𝒽𝑒𝓇 above 𝓈𝓂𝑜𝓀𝒾𝓃𝑔 𝑜𝓃 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝓉𝑜𝒾𝓁𝑒𝓉 and 𝑜𝓁𝒹 𝓈𝓀𝒾𝓃 but below 𝓃𝒾𝓅𝓅𝓁𝑒 𝓅𝒾𝑒𝒸𝑒𝒾𝓃𝑔𝓈, 𝓁𝑒𝑔𝓈, and 𝑔𝓇𝒶𝓈𝓈. Since playing the game I wondered how we might have dealt with a card that said An Absent Uncle, or A Disappeared Uncle, or if this would even register as a concern or desire.

I realised I had come across the figure of the uncle who had died of AIDS-related illnesses. A friend told me about her uncle who died of AIDS when she was a kid. He came from a large rural family in Pennsylvania and went to school in Pittsburg to study (mostly continental) philosophy in the 1980s. After he died, her aunt would send her his philosophy books, his name often written on the inside cover. She describes having found herself identifying with him, going on to study philosophy, fulfilling aspects of a life he was not entirely able to fulfil. After she told me this story, I realized how I had other friends whose uncles had died of AIDS at various points in the 1990s and 2000s. These uncles seemed so different to many of the uncles I have known. Towards the start of To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life (1990), Hervé Guibert describes, after his HIV/AIDS diagnosis, leaving his only friends and going to Rome where he knew no one. He begins to write the book, to construct a new friend, which becomes a companion who would also not save his life. Could this book also be an aunt or uncle, adopted or surrogate, for those of us without such an aunt or uncle in the first place?

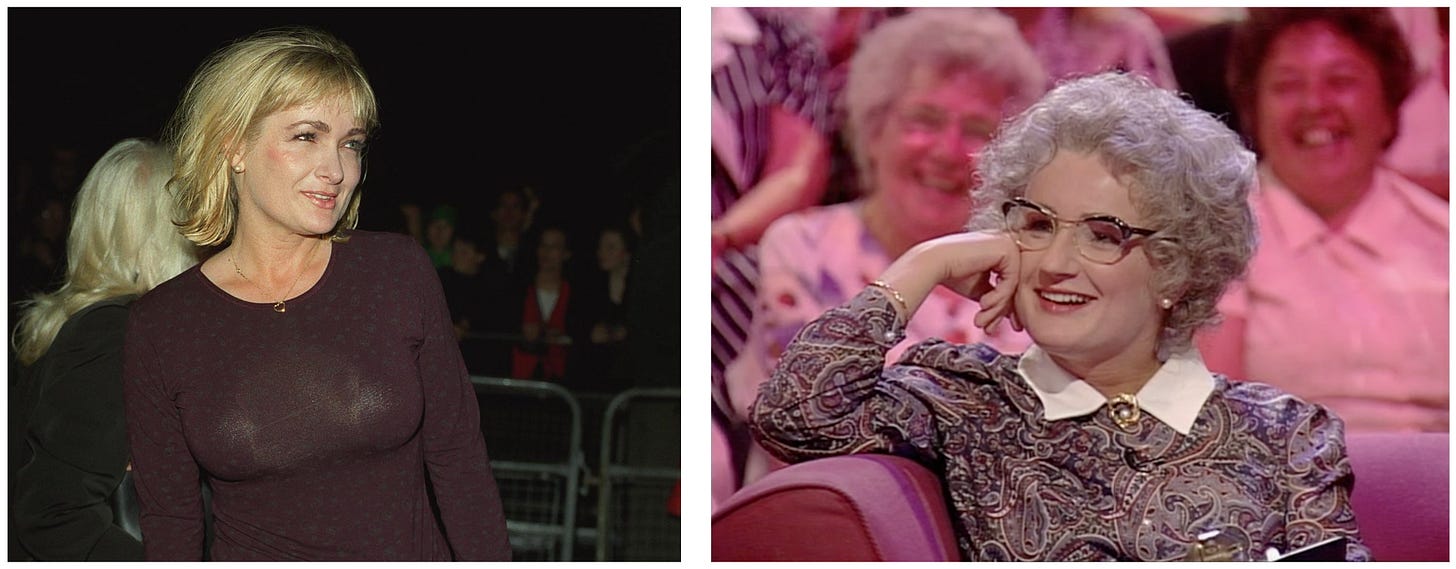

The other week I tried to write a paper about The Mrs Merton Show and the idea of old drag for a conference. As I was re-watching it a few months ago, after it came up on the BBC iPlayer, a memory came to me, perhaps a screen memory, that came to frame my thinking for this paper: a strange feeling I experienced as a young teenager, that involved an inability to imagine how I might dress as a 70-year-old. I became fixated on the idea that I would end up dressing the same as my grandmother, who was a similar age and style to Mrs Merton: in three-quarter length skirts, cardigans, with permed hair, a certain type of necklace, in soft wide shoes.

What struck me was this memory was gendered but also a desire. I wanted to (and in some ways still want to) be like my grandmother, and be with her and her friends. I thought about it not to re-claim it as a desire, but to assert that the notion of ageing as a process of negotiating or resisting contingency (very much the thesis of Simone de Bouvoir’s book on ageing); and that this notion can be countered with old drag. In the case of Mrs Merton, as in my memory, this took the form of a fixed acceleration. I became my grandmother as she became her mother. In the process, however, Caroline Aherne was able to transform what that identity felt like, and worked it through in the public sphere, as it was constituted at the time. She grants the audience not only a voice (literally), but the expression of sexuality, with irreverence, and also the possibility of politics outside the expected.

As I watched the show, I developed an affection for one of the regular guests in the audience called Horace. In an episode with Boy George, broadcast on 7 March 1997 (excerpt above), Horace tells an extended story about going to the sauna, and if he had gone to any of the saunas that Boy George had been to in London. After some research, I found his name was Horace Mendelsohn, as he tried to seek recompense from The News of the World after an article entitled ‘Mrs Merton made me into love god at 71’ went to print on 25 May 1997 (screenshot below). The fact that Horace is from Stockport, quite near Manchester, also near where Mrs Merton and my grandmother were from, made me think that he could be related to poet and former Angry Brigade member Anna Mendelssohn, and perhaps her uncle. I contacted various people who know Mendelssohn’s biography, but there is no such name on her family tree. I live, however, with the fantasy of this missing uncle.

Caroline Aherne died prematurely in 2016 at the age of 52. In this light, Mrs Merton (and this was my vague thesis in the paper), might be seen as a strange enactment of an older age that she wasn’t herself able to experience. Another case came up: Wayland Flowers, the puppeteer and illusionist who died prematurely of AIDS-related illnesses on 11 October 1988. His companion, the puppet Madame, similarly as outrageous as Mrs Merton, and perhaps forty years his senior can be seen, retrospectively, as a means someone used to be the old queen they weren’t ultimately able to become. This is partly an argument also about sexuality. In 1980, the actress Bea Arthur appeared in a sketch with Madame on a CBS comedy special. At one point Madame erratically looks around for something, or someone. Arthur asks ‘What’s up’, and Madame says ‘I’m looking for him, Hudson – I’m looking for a piece of that Rock’. Rock Hudson had just appeared on the same show. Arthur then says: ‘I’m sorry to sound catty, but isn’t there a slight age problem between you and Rock?’ There’s another pause and Madame says, with perfect delivery, ‘If he dies, he dies!’

The bitter irony is that Hudson did die, five years later, and his name appears on the same patch of the AIDS Memorial NAMES Quilt as Wayland Flowers (though spelt incorrectly) – both stars of very different kinds. Elizabeth Freedman uses another part of the quilt as central to her conceptualisation of queer time: ‘I had a fabulous time’, it says, emerging out of an orange bottle of laundry detergent – strangely like the advert before Madame’s appearance on the CBS special. Queer fabrication and confabulation, Freedman argues, are often performed in the present, acts that leave traces for what becomes the past, whether in chronicles, on TV screens, or upon quilts. But fabulation might also refer to a time recovered from the future – necessary when that future remained, and remains, unevenly uncertain.

To leave you with something, the drag conference was rounded off with Kareem Khubchandani, founder of various academic disciplines relating to the auntie: Critical Aunty Studies, Auntology, and Auntie (as in archive) Fever. I loved Kareem’s lecture so much and will leave you a talk by LaWhore Vagistan which discusses the role of the auntie: as aesthetic, mode, cypher, idiom, and ethic. I will keep trying to think about these questions so get in touch if anything resonates.

Additions:

┇

┇

┇

┇

┇

┇

┇

Anneke sent me this, which I wanted to add: Jordy Rosenberg on channelling his mother and gay Marxism.