Reading wrinkles

1.

Metoposcopy was a technique developed by Isaac Luria (1534–1572) that diagnosed the ‘status of the soul’ through the interpretation of hebraic letters on the forehead. It derived from the belief that ‘God brought all of creation into existence by means of thirty-two wondrous paths of wisdom. These thirty-two paths comprise the ten fundamental numbers, and the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet.’ Different letters appear on the forehead of those who have performed certain commandments and those who have not. The size and brightness also determined the reading. Whilst they could appear on other parts of the body—eyes, fingernails, even hair—the forehead had a particular correspondence to the zodiac. One of Luria’s disciples, Hayyim Vital (1543–1620), preserved several anecdotes metoposcopy in action. Looking at Vital’s forehead, Luria identified the letters alef (א), bet (ב), and gimel (ג), which demonstrated, according to Luria, the need to show greater compassion toward his father (אַבָּא). Through metoposcopy, structures of guilt (or absolution) are rendered visible, interpretable and evidential. Redemption and/or punishment follows.

2.

Though the father is a reoccurring figure in Charlotte Wolff’s books on sexology, she mentions only one father in her studies of hand-readings. Of the actor John Gielgud, she says that a highly developed upper part of his Mount of Venus (the baggy area just below the thumb) indicates an insoluble tie to either his father or his mother, who is the spiritual counterpart to his youthful, childlike, physiology. (The other night we watched John Gielgud in Jane Campion’s adaption of The Portrait of a Lady from 1999; a film in which Nicole Kidman often caresses fabric and holds her forehead.)

3.

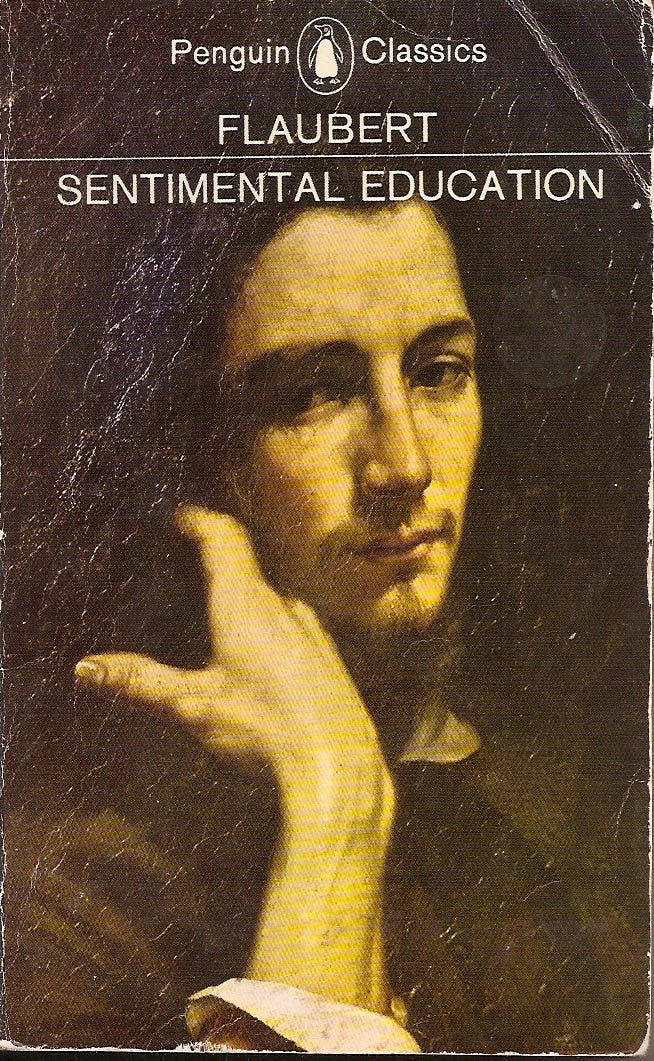

At the start of Ulrike Ottinger’s Madame X: An Absolute Ruler (1977), a number of the characters are called to join the lesbian ship Orlando. The second character to receive the command is Josephine de College, an international artist played by the international artist Yvonne Rainer. As she haphazardly roller-skates in what looks like the newly regenerated Kulturforum (just down from Potsdamer Platz in Berlin), the message falls from the sky: “CALL CHINESE ORLANDO – STOP – TO ALL WOMEN – STOP – OFFER WORLD FULL OF GOLD – STOP – LOVE – STOP – ADVENTURE – STOP – AT SEA – CALL CHINESE ORLANDO – STOP.” Rainer beams with delight, throws open her arms and skates away down a tree-lined avenue. A small white car pulls over. She skates over and a microphone appears from the front window. “We heard you’re going to join Madame X”, says someone inside: “What are your reasons for that?” She opens a books and reads into a microphone: “The wrinkles and creases on our faces are the registration of the great passions, insights, that called on us, but we, the masters, were not home.” She then shakes her head and says “Oh, that’s not it…” She then reads something else before turning to the pages of Flaubert’s Sentimental Education (1869). The quote rang a bell; I stopped the film to google it. It turns out it’s from Benjamin’s essay on Proust.

4.

In Rebecca Comay’s essay on Proust she talks about how Proust’s body, even after his death, maintained a certain youthfulness. The writer François Mauriac noted “the preternatural youthfulness of the corpse”: “Laid out on his bed, one would not have thought that he was fifty years old, but barely thirty, as if Time didn’t dare touch him who had tamed and vanquished it.” Paul Helleu, an artist, recorded: “Oh! It was horrible, but how handsome he was! He hadn’t eaten for five months, except for café au lait. You can’t imagine how beautiful … can be the corpse of a man who hasn’t eaten for such a long time; everything superfluous is dissolved away. Ah, he was handsome...” Man Ray’s portrait of Proust on his deathbed aids this interpretation; like a waxwork, without wrinkles, already a death mask.

Later in the essay, Comay elaborates on the Benjamin quote read in Madame X:

Far from being a legible surface on which we might decipher the traits of a stable character or impose narrative intelligibility on a lifetime, the face is revealed as an archive of accumulating omissions; the disfiguring streaks on our skin are just the alluvial deposits left in the wake of what was unlived.

She circles the argument back to time:

A wrinkle shows just how ambiguously time inscribes itself on our mortal bodies. Like every mark, it seems to hint of a discrete and datable moment of decision or incision, while ultimately frustrating the desire to identify any such moment. Even as it seems to bear the stamp of a punctual moment “in time,” to mark a singular here and now of inscription, its belated appearance points only to a prior passage “through time.” Appearing only belatedly, like a text written in invisible ink, the wrinkle is the perfect cipher of traumatic anachrony.

As such, for Comay, Proust managed to “erase the traces”, “not to overcome time in a moment of crystalline eternity” but “rather to unfold, or un-crease” or even “de-crease”. If wrinkles and creases are the marks of time, or more specifically of unfulfilled passions (and the lack of creases is their un-folding), then, who are the masters, and let’s hope they are never home.

5.

At the end of his chapter on gesture in Cruising Utopia (2009), José Esteban Muñoz cites Marcia Siegal’s At the Vanishing Points (1972), which claims that dance, not just gesture “exists as a perpetual vanishing point.” Gesture evaporates, according to Muñoz, “at the moment of its creation it is gone”. Patterns or repetition establish personality or character (terms beloved by the palmist) but gesture is forever in a fragile mode of their reproduction.

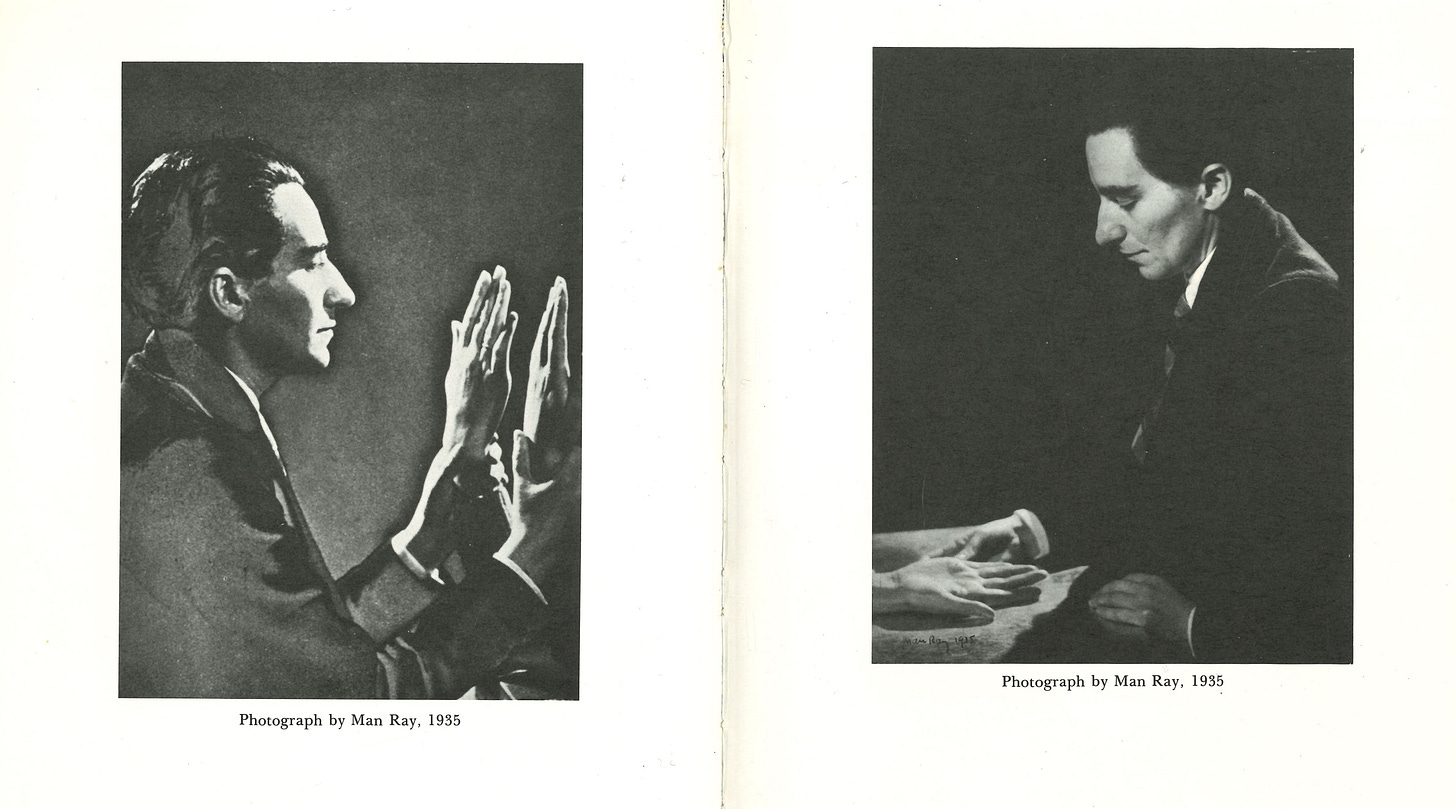

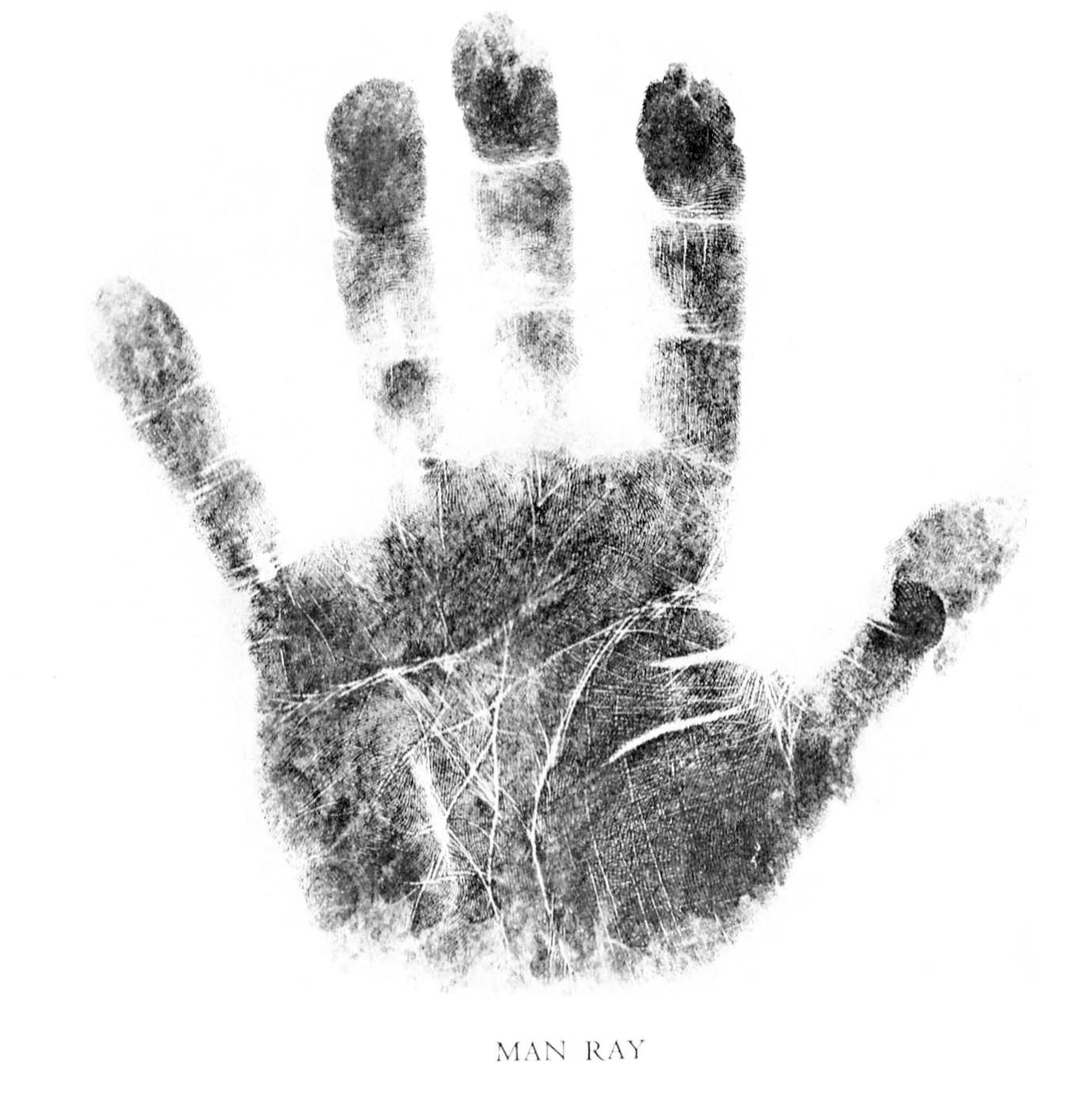

In 1935 Man Ray took two photographs of Charlotte Wolff reading hands. They are reproduced in her autobiography Hindsight from 1980. Likely in the same year, Wolff read Man Ray’s hands. She remarked that the “depth and clearness of the lines” are a sign of his “constructive powers.” His hand print remains in the archive. One wonders what she would have said of Proust’s line-less hands, if not his forehead?

What are Wolff’s handprints (including Man Ray’s) other than the petrification of gesture, the arrest of movement, the manifestation of finitude? In the introduction to A Psychology of Gesture (1945), she writes that her previous work in The Human Hand (1942), excluded the “dynamic aspect” of gesture. Handwriting too can be read as a chain of “crystallised gesture”, she says. But it is gesture, for Wolff, that leads to creases and lines in the hands. As such, the vanishing point is mapped onto itself: onto the hand, the body, as a map of previous movement, a log of gesture.

This points towards a utopianism of gesture. The gestural, according to Muñoz, “speaks to that which is, to use Ernst Bloch’s phrase, the not-yet-here. The gesture is not the coherence or totality of movement.” It is the fractures of a future barely detectable. If the gestural speaks to something not yet evidenced, the hand print registers a frozen forensics of the future.

⦚

This was something I tried to write about a couple of years ago for a paper at a conference on queer modernism at Oxford.

Looking back, I found this note, all in caps at the end of the paper: THE HANDPRINTS ARE THE DEATH MASK OF GESTURE. THEY POINT TO A DYNAMISM THAT HAS CONGEALED INTO A LEDGER OF EVIDENCE. THE POINT MIGHT BE TO DEVELOP A TECHNIQUE OF HAND READING THAT IS NOT ONLY FUTURE-ORIENTATED BUT OPEN TO THE EVAPORATION OF ITS FORM. I’m (still) not so sure how far I got with the idea.

6.

On lines on the face. A L'Oréal advert with Natalie Imbruglia from 2002-03 has always stuck in my head. She was facing thirty, an age I have now long faced:

According to the ideas or theories above, I have compiled an exhaustive list of all the possible reasons to get rid of wrinkles, or not get rid of them:

The escape the judgement of the metoposcoper/chiromancer.

To receive a different judgement from the metoposcoper/chiromancer.

To move differently/to have moved differently.

To indulge in heresy, sinfulness, and refuse obligation.

To pretend you have met your obligations.

To appear different.

To escape the archive of the state and its agents.

To face thirty, or another age.

To wipe away the marks of failed desire.

To create new marks of failed desire.

To only drink café au lait.

To wipe away the marks of past movement.

To work differently/to have worked differently.

Thanks for reading! On metoposcopy, see this essay by Lawrence Fine. Rebecca Comay’s incredible essay on Proust, something I’ve read over and over again, is available here. Let me know if you have any thoughts/reactions. I’m interested think more about age and ageing and this representations. What adverts do you remember from 2002-3?